Methods

Our 12-month project included partnerships with three LTC homes, an advisory group of key stakeholders (most of whom were leaders of organizations that supported the provincial LTC sector, along with leaders and essential care partners from the participating homes), and several LTC residents and family members. To help guide our work, we undertook a rapid scoping review (

Palubiski et al. 2022) to identify relevant literature concerning family caregivers entering into LTC homes during emergency conditions. Our review found that existing evidence was based primarily on expert opinion (

Palubiski et al. 2022).

The three homes in our study were implementing a designated care partner (DCP) intervention to allow some family members to enter the home during the pandemic. This DCP program was an LTC adaptation of the Caregiver ID Program (developed by The Change Foundation and Ontario Caregiver Organization) and the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement's “better together” process (

Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement 2020;

Ontario Caregiver Organization n.d.). The DCP program includes a process to identify essential care partners who provide personal, social, psychological, emotional, and physical support for residents. The program includes orientation and training, a commitment to follow safety protocols and use ID badges, and access to essential care partners to the home.

We were introduced to the leaders of the three homes by members of our advisory group. We shared our research objectives and methods with these leaders, answered questions, and then reached an agreement to work together. That agreement included the stipulation that participation in our project would be entirely voluntary for all employees working in the homes, as well as residents living in the homes and their essential care partners.

In November 2020, we learned that our proposal had been accepted and we received funds to conduct our work over a 12-month period.

Our group followed a DE approach (

Fagen et al. 2011;

Patton 2011), drawing on our group's prior experience with this method (

Conklin et al. 2015;

Elliott and Stolee 2015). DE is based on the notion that human systems (such as LTC homes) are complex adaptive systems and is focused on the way in which people intend to use the results of the evaluation (

Patton 2011,

2017). This evaluation method is suited to situations that are ill-defined and characterized by high levels of uncertainty, such as the effort to enhance health and well-being in a LTC home during a global pandemic. DE also creates a social learning environment that informs effective action to bring about positive change, and is thus aligned with organizational change theories that posit that change agents must often produce learning that brings about improvement and transformation (

Argyris and Schön 1978;

Patton 2011;

Conklin 2021). We selected DE as the project's implementation approach because it was well suited to the complex situation faced by the three homes we had partnered with and because the leaders of these homes were both sympathetic to and had experience with the use of social learning processes to facilitate positive change (the homes were participating in a learning collaborative coordinated by one of the organizations in our advisory group).

We used DE to enable a continuous improvement process as the homes implemented their DCP interventions. DE recognizes that given the complexity of human systems, interventions need to be tailored to the unique features of specific social environments (

Hummelbrunner 2011;

Patton 2011;

Kania et al. 2012). In essence, a DE approach sees evaluators collect data about the intervention's operation within a complex milieu and then use the data to help the program team make improvements (

McLaughlin 1976;

Patton 2011).

We created DE core teams (DECTs) in each of the three participating LTC homes to provide oversight and assistance to our DE process. The DECTs were composed of representatives of the LTC homes' management as well as DCPs and residents who were involved in the DCP program. One person on each DECT was designated as our “primary contact” in the home (in all three homes, the person taking this role was a staff member at a program management level). DECT membership includes the following:

•

Home 1: Two DCPs, one resident, one corporate vice president, and a program director (five members).

•

Home 2: Two DCPs and one administrative staff from the participating home (three members).

•

Home 3: One DCP, one resident, one manager from the participating home, and one corporate representative (four members).

We originally intended to bring the three DECTs together in combined planning meetings and feedback sessions so they could hear about what was happening in the other homes. However, the exigencies of the pandemic made this impossible. When we began the DE work, one home was dealing with a COVID-19 outbreak, another was finalizing organizational changes, and only one home was ready to begin. The DE process was therefore governed by different timelines in each home, and it was not possible to jointly plan and debrief each DE iteration with all three homes at the same time. However, we did allow for sharing across the homes through the regular meetings of our advisory group (which included representatives from each home).

The DE process involved initial planning meetings, an inquiry process that implemented the plans, and feedback sessions where findings were shared and new plans were created. We had intended to carry out five iterations of this process with each home. Again, the realities of the pandemic intervened, and we ended up completing two iterations with two homes and three with one home.

During initial planning meetings, the DECTs identified questions and concerns they wanted the research team to investigate. In subsequent DECT feedback sessions, findings were presented, and the DECTs considered improvements to their implementation process and established new questions for the researchers to investigate in the next DE iteration. All DECT meetings were held on the Zoom videoconferencing platform.

The research team initially intended to recruit five DCPs and five staff members at each LTC home (thirty participants across the three homes). The DECTs and research team agreed that this would provide an appropriate range of diverse experiences to reveal facilitators and barriers to the implementation of the DCP program. In this case, however, our results exceeded our expectations, and we recruited 65 participants (34 staff and 31 DCPs). Participating staff were directly involved with the DCP program, representing various roles within the home: registered nurses, registered practical nurses, personal support workers (PSWs; other jurisdictions term this role Health Care Aide or Resident Care Aide), therapeutic recreation staff, managers, dieticians, pastoral care workers, and Behavioural Supports Ontario staff (a provincial team specializing in dementia care).

Before our DE began, each home's primary contact announced the project to potential participants (including residents, family members, and staff who were participating in the DCP program). Interested people were invited to contact the research team. After obtaining informed consent, the research team conducted interviews (using protocols developed in collaboration with the DECTs) in the individual's language of choice—English or French.

Interviews, approximately 30 min long, were conducted by Zoom or telephone. If participants consented, interviews were audio-recorded, and the interviewer created detailed notes while listening to the recording after the interview was complete. If the participant did not consent to a recording, the interviewer made detailed notes on a computer during the interview. Interview notes were later anonymized.

During subsequent iterations, the research team approached people who had signed consent forms. Some participants were interviewed once, while others were interviewed up to three times.

We used two analytical procedures. The first allowed us to work quickly and produce results that the DECTs used to consider real-time improvements to their implementation process and also to generate new questions about the functioning of the program. The second procedure was used when all iterations were complete and all DECT feedback sessions had been held. This procedure was intended to take another look at the data to ensure our rapid process had revealed all relevant meanings latent in the data set.

Our first analytical procedure involved a deductive (directed) coding approach, and the second used an inductive (open-ended) coding and theming approach (

Hsieh and Shannon 2005;

Braun and Clarke 2006;

Patton 2015). Together, these procedures allowed us to find answers to the questions posed by the DECTs and also to consider whether the data set could support additional insights about the DCP programs in the participating homes. This paper reports the overall findings from both analytical procedures.

A comprehensive written record of each interview was created based on the interview notes and recordings. The data were imported separately for each LTC home into NVivo software for analysis. One analyst (MM) used the interview questions as nodes and proceeded to code participant data (see Supplementary Material 1 for the interview protocols).

After coding was complete, the analyst prepared a detailed findings report. The reports were organized with interview questions as headings, followed by a description of interview responses to the question. This report was reviewed by a second (JC) and sometimes a third (JE) analyst, who identified areas needing further consideration. The report was then finalized. Two researchers (JC and MM) met with the home's DECT to share findings, facilitate a discussion of possible improvements to the DCP implementation process, and identify new questions that could be the basis for the subsequent DE iteration.

For the second analytical procedure, one member of the research team (JE) reviewed the interview audio recordings and considered whether the seven findings reports (one for each iteration at the three homes) were a clear and complete presentation of the meaning of the data. This exercise served to confirm the findings and conclusions in the reports. The exercise also allowed the team to extract some illustrative quotations for the main findings. Then, using an inductive approach, the research team coded all reports to identify themes characteristic of the three homes.

Details on our qualitative methods can be found in Supplementary Material 2.

The research protocols were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Bruyère Research Institute (REB protocol M16-20-068) and the University Human Research Ethics Committee of Concordia University (certificate 30014706).

Discussion and conclusions

This research responds to recent calls for interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (

Meisner et al. 2020).

Wister and Speechley (2020) issued a specific challenge for research that examined the positive adaptations of people and communities to the pandemic. Our DE approach provided an opportunity for positive adaptations in three LTC homes.

Our most significant finding is the recognition by virtually all participants of the importance of the care provided by DCPs. This care is

essential. The DCP program was viewed by almost all participants as a success. Our participating homes are now considering how the DCP program might be institutionalized and how to better support the care provided by family and friends. Our findings are consistent with recent studies confirming the importance of care provided by family (

Kemp 2021) and also confirm studies showing that LTC homes that responded proactively and creatively to the pandemic have fostered a variety of positive outcomes for residents and families (

Palacios-Ceña et al. 2021;

Gallant et al. 2022). The findings reported here also support studies suggesting that attitudes toward the care provided by families may be changing and that the conditions may now be in place to transition the culture of LTC homes toward patient-centred care that emphasizes selfhood, human relationships, and strengthened partnerships between staff, family, and those who receive care (

Kemp 2021;

Mackenzie 2022).

Our findings also confirm that DCPs recognize that the care provided by frontline workers, especially PSWs, is essential and are aware of challenges (related to workload, working conditions, and pay scales) that make the work of PSWs difficult. Many DCPs stated that they recognize that the LTC sector needs additional resourcing to improve basic care and PSW work conditions. These findings are consistent with studies showing that when families were barred from LTC homes, the workload of staff increased, sometimes leading to exhaustion and burnout (

Hugelius et al. 2021;

Low et al. 2021;

Palacios-Ceña et al. 2021;

Smaling et al. 2022).

The growing recognition of the importance of care provided by DCPs and the likelihood that health leaders may be exploring ways to support that care could have the unintended consequence of reducing pressure on the government and managers to increase basic care resources in LTC homes. This report is not intended to disparage the importance of basic care provided by PSWs and other staff, but rather to highlight the need for a new partnership and for better LTC resourcing.

Our work has also brought to light some pragmatic findings about implementing a visitation program such as the DCP program. In our participating homes, DCP training, communication, and informal interactions were considered to be “good enough” during the pandemic, although participants suggested areas for improvement. The one-size-fits-all approach to training could be improved by tailoring training to the needs of specific residents and DCPs. Moreover, training updates should be offered when circumstances change. Those responsible for communications should analyze DCP communication requirements and should highlight the most important information for easy access. DCPs also often need to interact with staff during visits, and finding ways to normalize and support these interactions is important.

Our findings suggest that every LTC resident needs a DCP, and when possible, a resident should have multiple DCPs who provide care ranging from the psycho-social support that occurs when people spend time together to some elements of basic care such as feeding, bathing, and grooming residents. DCPs also monitor the health of residents; by spending time with a resident, they often notice new situations that they bring to the attention of staff. DCP participants also told us that there were times when staff were reluctant to listen or take action. DCPs stated that they must advocate on behalf of the resident, ensuring that LTC health care staff take note of situations requiring action. This is consistent with the findings from

Dupuis-Blanchard and colleagues (2021), which reveal the importance of family members’ advocacy roles.

Although our findings indicate the overall success of these DCP programs, they also reveal a general and pervasive deficit in care.

Table 2 shows the thematic summary that resulted from our analysis. These themes represent the patterns of thought, behaviour, and structuring characteristic of the situation in our participating homes. The themes, in other words, correlate with the prevailing situation and can be called upon to describe specific aspects of that situation. They are part of a web of behaviour, or more specifically, a web of sensemaking behaviour, which

is the reality of these social milieus.

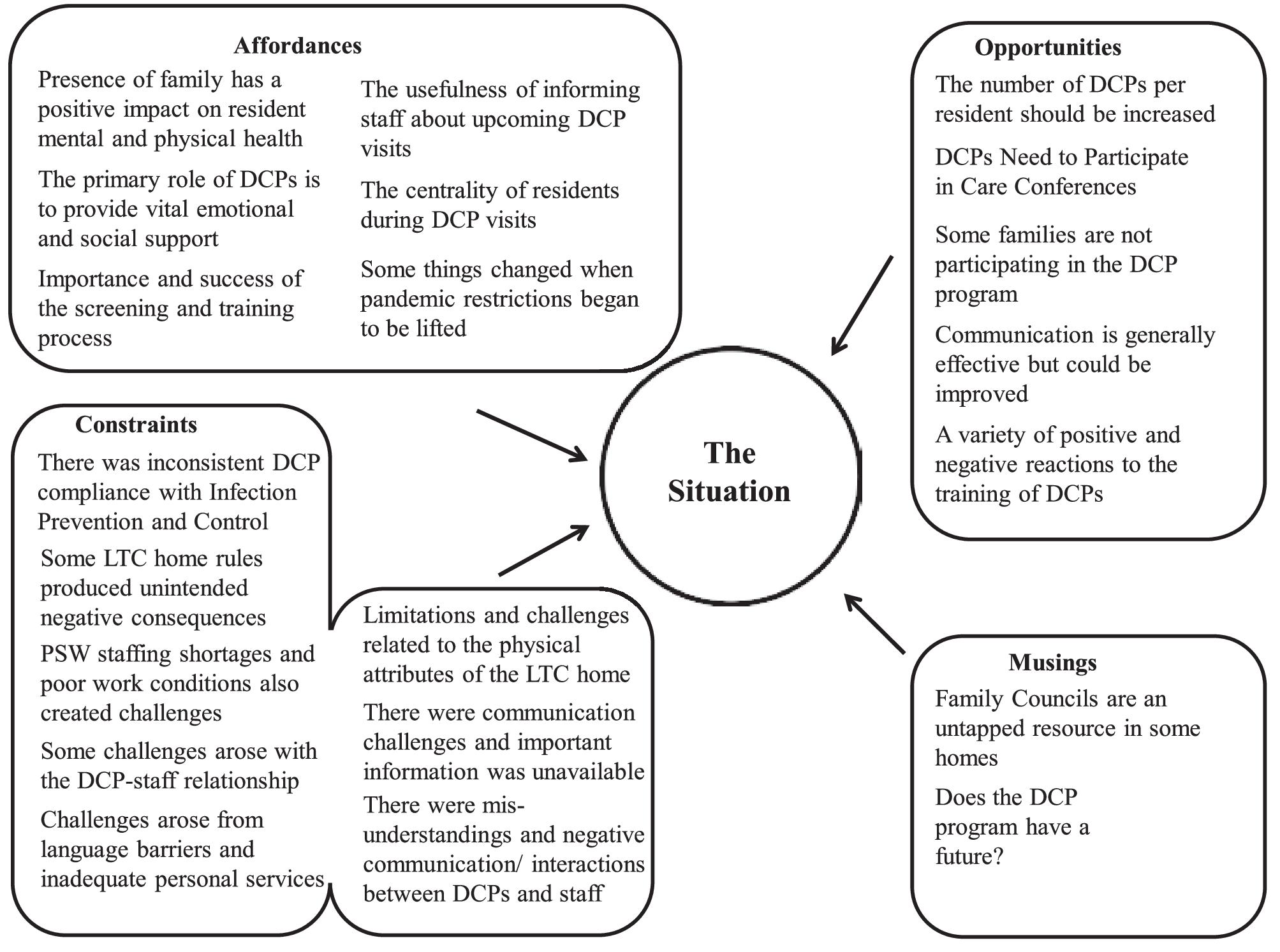

Clustering these themes can reveal additional meanings. For example,

Fig. 1 suggests that some themes reveal the affordances of the situation they describe—the congenial aspects and positive outcomes characteristic of the homes. Other themes reveal constraints, limitations, and challenges. Other themes reveal opportunities to improve, and still others represent musings within these human systems about their future.

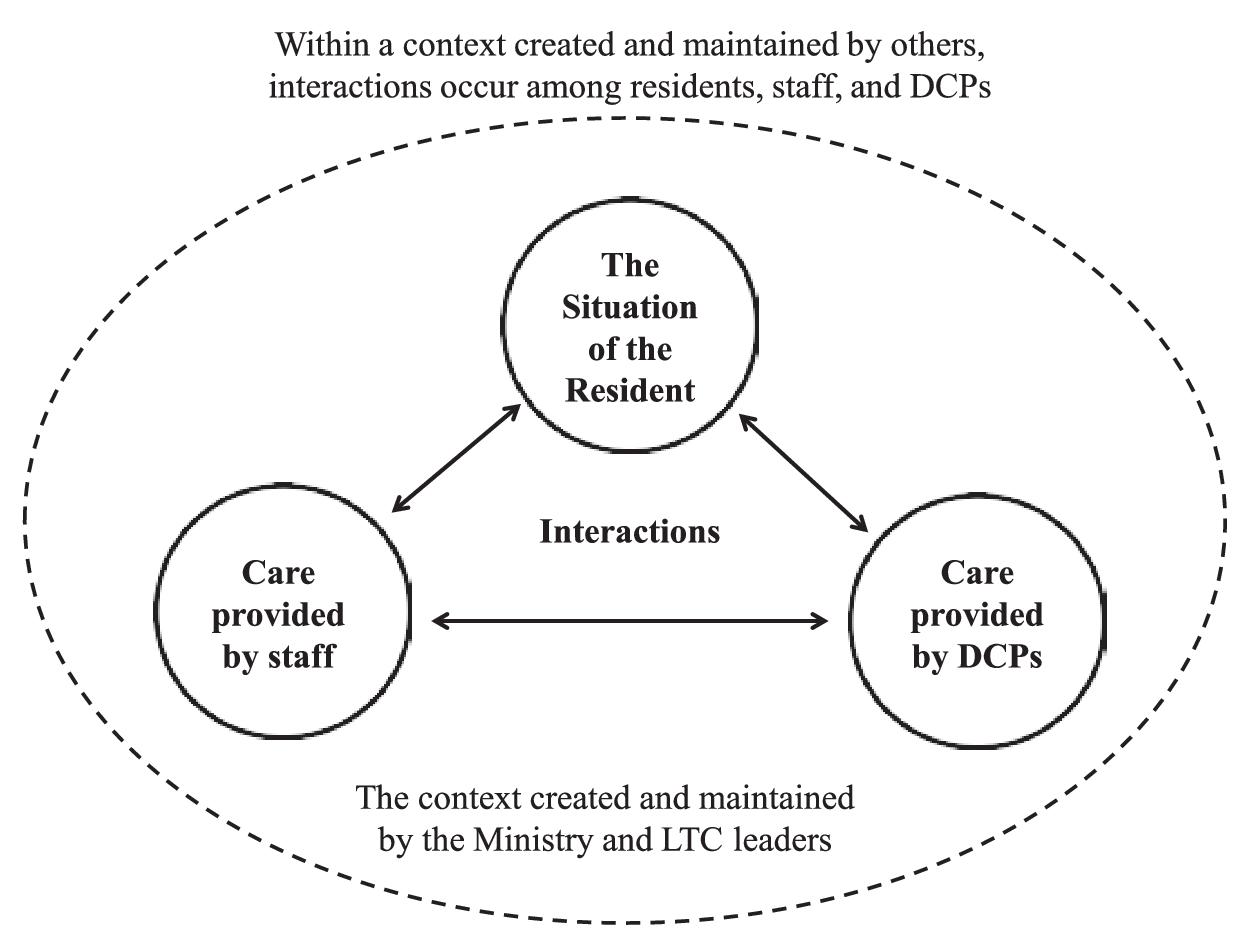

The situation depicted by these factors sees ongoing interactions among residents, staff, and DCPs, and these interactions often have to do with providing and receiving care as well as an ongoing effort to respect the dignity of the resident, the frontline staff, and the DCP as they seek to support their residents (see

Fig. 2). We might also say that the themes reveal a relational context—a web of relationships among residents, staff, and DCPs within a context that is created and maintained by health officials who set and enforce the standards of care and by LTC leaders who manage budgets and work routines.

Ultimately, the themes reveal a social world in which a natural partnership between those providing care is not able to take hold, where a deficit of care is experienced by too many, and where these shortfalls are institutionalized in a system that is founded on a mindset of accountability and compliance rather than one of learning and relational care. Paid and unpaid care providers struggle to meet the needs of residents who seek care and to form strong and supportive partnerships to meet those needs. Some residents languish in isolation and neglect, and the LTC milieu fails to provide an adequate “holding environment” to support those who are providing and receiving care (

Kahn 2001,

2005,

2019;

Conklin 2009;

Barton and Kahn 2019).

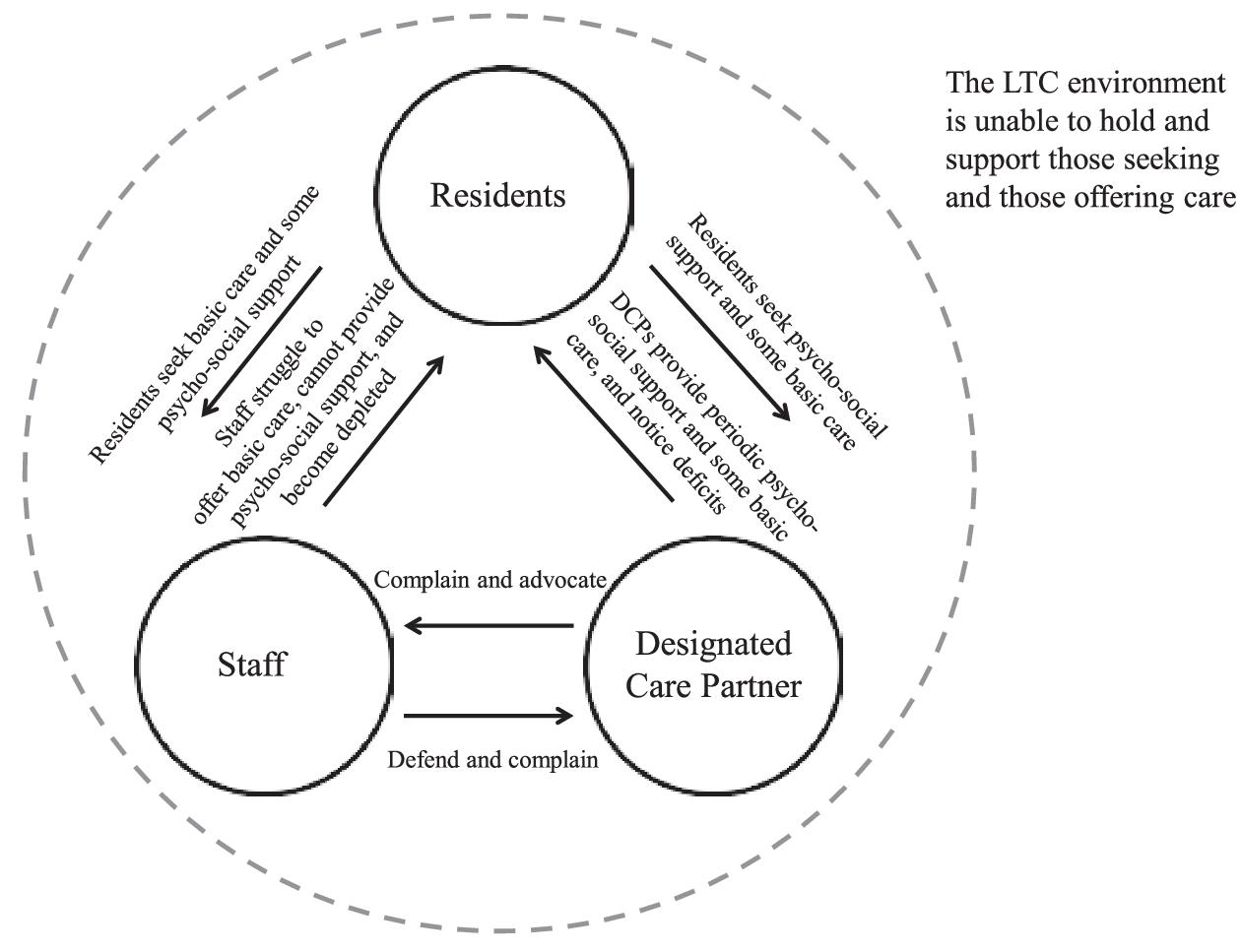

Figure 3 reveals this ongoing, unwholesome dynamic.

Residents need care, and these needs are satisfied first by the care providers employed by the LTC home. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, this care often failed to meet residents’ needs, and the shortfall was attended to (for some residents) by the efforts of DCPs who met some psycho-social needs and helped with the resident's basic care. This compensatory care provided by DCPs was offered without the benefit of a full partnership with caregiving staff, and gaps frequently appeared in the form of unmet needs. These gaps arose in part because the resident's health and well-being are not static but continue to change as the resident ages and adapts to the LTC milieu, creating the need for DCPs to become advocates who call attention to the care deficits that undermine a resident's health and well-being.

Moreover, the experience of providing care during the pandemic caused staff and DCP caregivers to become depleted. They thus encountered the need to be restored and made whole again. Because these caregivers at times act more as adversaries than partners, they do not adequately support each other. In addition, the LTC home is not able to adequately support the caregivers, given the need to focus on Ontario's fulsome LTC compliance regime and on an array of new and changing pandemic requirements and to deliver care within a tightly controlled and inflexible budget. Acrimony and disputes arose between paid and unpaid caregivers, and LTC leaders sought to manage these conflicts and maintain stability within the hard-pressed workplace. The result was an unhealthy and depleting dynamic within some LTC homes where groups with the potential to become partners instead functioned as adversaries and where leaders were able to do little more than resolve disputes and do their best to comply with standards imposed by external authorities.

We offer this model as a contribution to the growing conversation about how to improve the LTC sector in Canada and other developed countries. The resident needs care; this care must be improved, and one of the most immediate ways of promoting this goal is to create the conditions for a new partnership between LTC frontline staff and DCPs. In addition, LTC leaders must recognize the needs of frontline staff, and these needs must be better understood and attended to. DCPs often also have challenges and needs, and these must be considered as well.

Our final suggestion is that efforts to improve the LTC sector must be carried out with the meaningful participation of all key stakeholders, including family members and frontline staff, in all aspects of program design and implementation. For decades, the social science of organizational change has shown that meaningful stakeholder participation is a factor critical to the success of change initiatives. As early as 1960,

White and Lippitt asserted that “Of all the generalizations growing out of the experimental study of groups, one of the most broadly and firmly established is that the members of a group tend to be more satisfied if they have at least some feeling of participation in its decisions” (1960, p. 260). Recent studies confirm that the principle of stakeholder participation is often associated with successful efforts to introduce improvements in organizational milieus (

Stouten et al. 2018). Our findings include observations from participants indicating that the ability to participate in the design and operation of the DCP program contributed to more positive feelings toward the program. This provides support for the suggestions of

Cosco et al. (2021) and

Meisner et al. (2020) about the role of co-design approaches in addressing the social isolation and other challenges experienced by older adults as a result of the pandemic.

Co-design and collaboration were also characteristics of how we carried out our DE process and produced the results that are reported here. Our experience confirms that DE is well suited to inquiries into highly uncertain and complex social phenomena (

Patton 2011;

Conklin 2021). As policymakers consider how to design and implement improvements in LTC homes and processes as a result of our pandemic experience, we suggest that serious attention be paid to the utility of social learning processes such as DE.

A new and supportive partnership between staff and families is one of the needed improvements in the LTC sector, and the process to design and implement this improvement must itself be based on a spirit of partnership and collaboration.